This is a story about nature, man, resource management, and the challenges and repercussions of trying to bring order out of the wild.

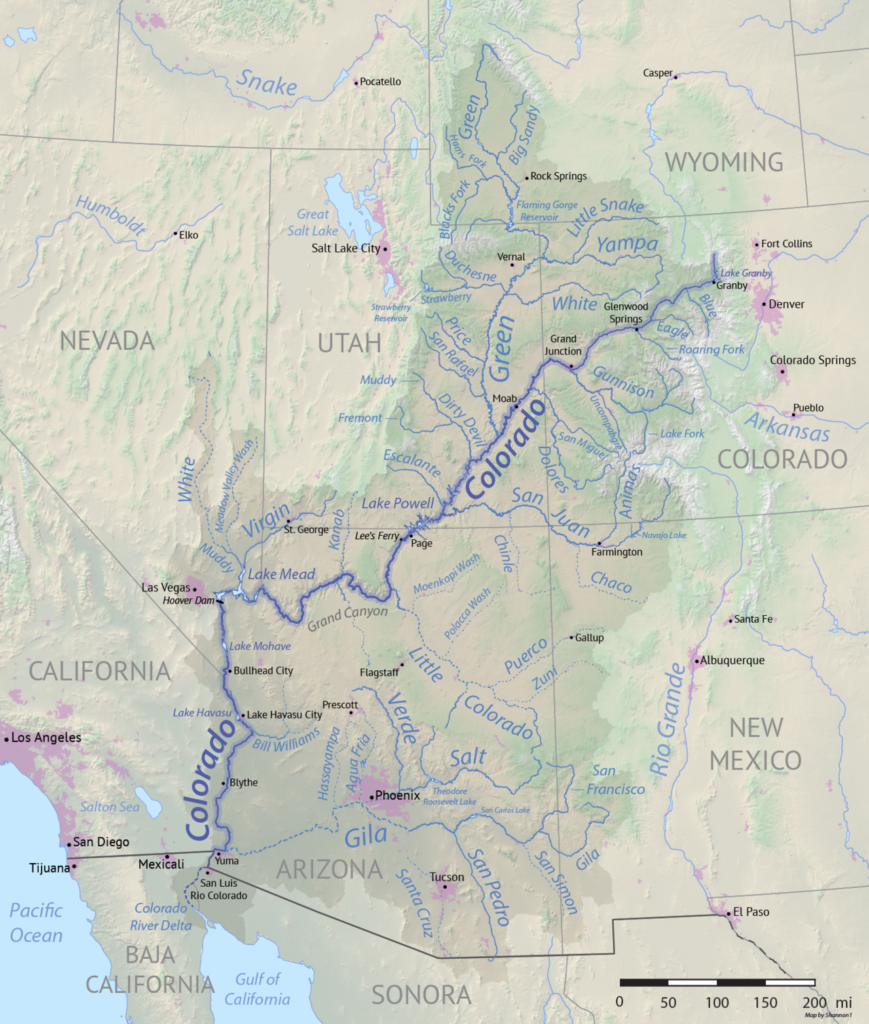

The Colorado River begins in the southern Rockies. Tumbling down those mountains for hundreds of miles, the river swells as it is joined by numerous tributaries before leveling out across the arid Four Corners region. The river blasts through Utah’s slickrock, carving impossibly deep and twisting gorges out of the living stone to make this area one of the most inaccessible regions of the continental United States. The remoteness of this area essentially sealed its fate and we’ll read more about that further down.

The river continues through Utah into Arizona, Nevada, and California before fanning out across the northern portion of Baja California and ultimately draining into the Sea of Cortez.

Evidence of human contact with the river goes back 12,000 years, the end of the last glacial period. Much time has passed, and our dependence on the river has only grown.

With that demand comes the need for regulation. Back in 1922, the Colorado River Compact was signed to divide its waters across seven states. It was amended in 1944 to ensure a viable flow rate into Mexico.

But a river is a wild thing. There are dry years and wet years. Add to this the inevitable growth of agriculture and industry, all of it dependent on massive amounts of fresh, flowing water.

Look at the map above, along the river just at the Arizona/Utah border. You’ll find a spot called Lee’s Ferry. The states above that point are referred to as the Upper Basin. The states below represent the river’s Lower Basin.

The Lower Basin states remain at greatest risk where the flow of water is concerned and this is where the engineers and architects of the world start to think about dams.

And this one would be a doozy.

With considerable controversy, construction of the Glen Canyon Dam began in 1956. It took seven years to complete and in 1963, the waters of the Colorado River began to back up creating Lake Powell, the second largest reservoir in the United States while essentially swallowing tens of thousands (if not millions) of years of natural and archeological history.

Some environmentalists decry the ecological devastation, the loss of habitat and history. While the dam was erected to ensure a consistent water supply to the Lower Basin states, critics report that enough water is lost annually through lake evaporation to meet the needs of Los Angeles.

Others suggest that the hydroelectric capabilities of the dam make it a premier example of renewable energy. And of course we all take full advantage of the abundant water that runs from our taps, the electric power that charges our devices, and the plethora of foods in the marketplace.

One thing is for certain. Almost nobody knew about this place until the dam. Even the conservationists (Sierra Club) who lobbied against damming the Colorado River back in the 40s and 50s finally agreed to a dam, so long as it was built here, right above Lee’s Ferry.

Why?

Essentially because they had never been there. Once the dam was under construction and they saw the waters rising, the then-leader of the Sierra Club, David Brower, recognized the concession as his life’s biggest regret.

With the creation of Lake Powell and what has since become known as the Glen Canyon National Recreational Area, the region sees upwards of two-million visitors annually.

Relationships are complicated. We often celebrate the notion of “pristine” wilderness. As a construct, it suggests that human engagement with the wild world becomes, at some point, profane.

But what is that tipping point? How many people are required to come into contact with a place before it is no longer “pristine?”

I am suspicious of a mindset that sets human affairs apart from the rest of Creation. The idea of a virgin wilderness losing her flower to the rapacious tendencies of lusty man, while not entirely untrue, is grossly oversimplified.

There is more to the story. All of creation moves along the path of least resistance with agendas of self-interest that are mutually opposed. This is what underlies the idea of “order” or “balance” in the natural world.

It is not elegant. It is magnificently violent.

Mankind does not differ from the rest of creation in our zealous self-interest. We are just jarringly efficient. And we are aware of this efficiency which, under optimal circumstances, is the beginning of responsibility and awareness.

Without doubt, there are elements of our human history lost beneath the waters of Lake Powell. There are geological wonders that have been flooded out of existence. Conceptually, it sounds tragic.

But if there is no one there to offer witness to these precious things, what then is the basis for advocacy and preservation? If we do not trespass, if only to offer testimony on behalf of the landscape and the miracles it might suggest, how can we stoke the fires of conservation and stewardship?

Lake Powell is only 57 years old. Though quite young, my guess is that many (if not all) of the participants of D&T Grrrl! 2020 were not yet born when the lake was created. These were decisions made by another generation.

It is essential that you go there. That you bear witness. That you experience the water and the earth and the sky.

And then you may come back and tell us: were we wrong to flood the canyons that so few had ever encountered?

Or is there benefit to bringing people into connection with this place so that, perhaps, more considered decisions might be made in the future?

Leave a comment below for posterity or join us in the D&T Chautaqua Discord to discuss this post with other adventurous spirits from around the world.

Just saw this post … those are some heavy thoughts to ponder. It certainly will lend a deeper appreciation to the experience, an appreciation of the magnificence of natural creation, and what our human tinkerings bring.

My father was involved in building the Glen Canyon dam; the bridge iver the canyon and later the piwer plant in Page Arizona. He was involved in many of the necessary projects across the west during the 50-70’s including the Bridge over Prudo Bay at the top of the Al-Can Pipeline … other necessary projects. It is troubling to me that beopke who viuce against such projects daily utilize services provided by such projects. Its seems short sighted to be destroyers of what the great building generations built! Iguess that is a lesson fir life. We all need to choise rather we will be a builder; a destroyer ir simply a spectator! MarLa Mari (Holt) Kepler Daughter of LaMar William Holt I speak up fir him and others who sacrificed in many ways because they believed they were helping to build a supporting infrastructure for a great and growing nation.Men lost their lives building that dam. I hinor those list lives and my fathers great injuries while building that dam which earned him the Navajo name from his co-workers which means: dead man who walks. ( sp? Najaishiby) because he went back to work after just 21 days in the hospital.. men then didnt go on disability. They put them selves back to work. That is the tyoe of men and heart tgat built these great projects that some want to destroy with little or no effort at true understanding.

Thank you for your comment MarLa. It’s an honor that you would reach out and share your father’s legacy with us. I’m excited that in drafting this blog post I have been allowed to connect with the history of the dam through your comment and your father’s efforts.

It’s a complicated situation with no easy answers. I certainly did not restrict myself to any conclusions. Yes- geologic and human history was lost with the building of the dam, but as you mentioned so many people continue to benefit from the hydroelectric power produced by the dam.

What’s the priority? Preserving history or attending to the needs of the moment? I think we all agree that if possible, we might try and do both, but few things are ever that simple.

Your father would be proud that you continue to advocate for him and the other builders of his time.

I found this recently🥰