I came across a fascinating article written by Helen Macdonald, the bestselling author of H is for Hawk, a memoir of her time adopting and raising a goshawk. Her lastest collection of essays, Vesper Flights, is due out in August.

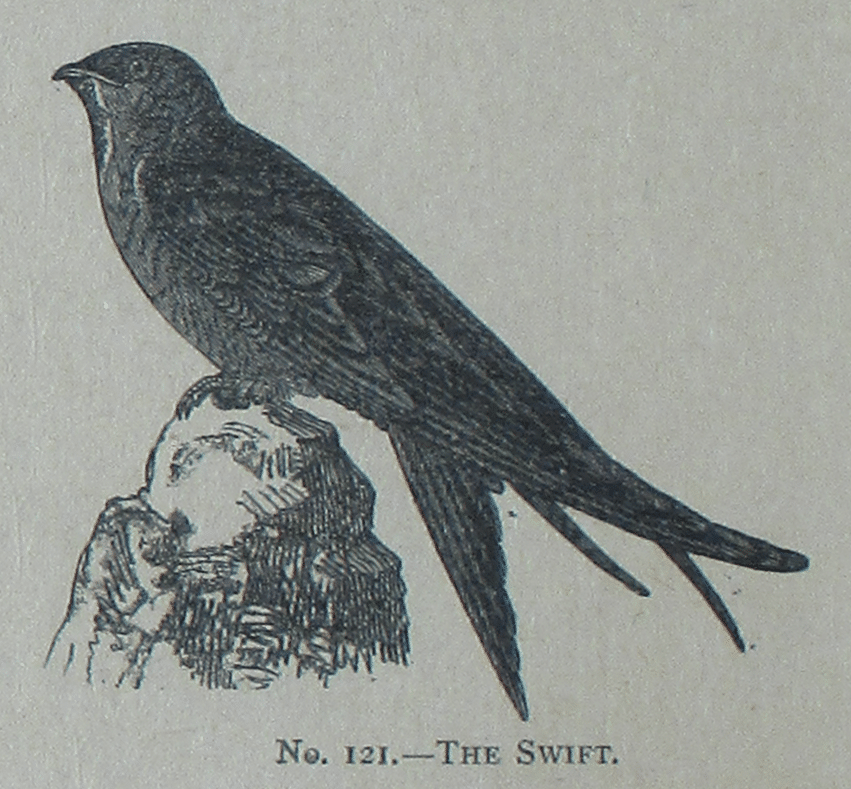

The swift is a bird I know nothing about, and that’s shocking given the incredible attributes of this aerial phantom. It is among the fastest of birds, some species reaching speeds of over 100 mph in flight (169 km/h). They spend so much time in the air that over a lifetime, the common swift is believed to cover enough distance to make it to the moon and back five times over.

Macdonald opens her meditation with some vexation:

When I was young, I was frustrated that there was no way for me to know them better. They were so fast that it was impossible to focus on their facial expressions or watch them preen through binoculars. They were only ever flickering silhouettes at 30, 40, 50 miles an hour, a shoal of birds, a pouring sheaf of identical black grains against bright clouds.

Her musings of a life on the wing are fascinating. Breeding and hunting and even a special kind of sleep all take place in the sky with the swift only ever coming down to nest for a roughly three-week period. Her perhaps most moving reflection is on the so-called “vespers flight” of the swift:

. . . all at once, as if summoned by a call or a bell, they fall silent and rise higher and higher until they disappear from view. These ascents are called vespers flights, or vesper flights, after the Latin vesper for evening. Vespers are evening devotional prayers, the last and most solemn of the day, and I have always thought “vesper flights” the most beautiful phrase, an ever-falling blue.

This ritual is repeated again at dawn, nautical twilight to be exact, in an aerial dance that coincides very nicely with the predawn and sunset prayers of Muslims.

What scientists are learning about the nature and purpose of these flights is even more fascinating and I encourage you to read the entire article here.

Leave a comment below for posterity or join us in the D&T Chautaqua Discord to discuss this post with other adventurous spirits from around the world.

As always, well written article about a very interesting being. Your article is thought provoking. It reminded me of poems by Allama Mohammed Iqbal, poet / philosopher from Pakistan / India. He is known as the reincarnation or continuation of Rumi. He frequently refers to “Shaheen” in his poetry. I believe it refers to Hawk, Eagle, Falcon, because to the layman like me, they seem to be all in the same family. Some of these are well known verses or couplets, some of which we were required to memorize, from our Urdu text books. I think he wrote more in Farsi than in Urdu. In Iran he is well known as Iqbal Lahori. As he resided in the historical city of Lahore, where is shrine is, right at the entrance of the Badshahi masjid.

Shaheen kabhi parwaz say thak kar naheen girta:

The eagle never falls down because of being tired.

Tu Shaheen hay, parwaz hay kaam tera:

You are a hawk, your work is to fly.

And this one, sung by Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan:

Naheen tera nashayman qasr-e-sultani kay gunbad par

Tu Shaheen hay basayra kar pahaRRon ki chatano’n par

You nest (home) is not on the domes of the palaces of kings

You are a falcon, hang out in the high cliffs of mountans

The first line also refers to the crowd, most people: pigeons hang out in warmth of the crowd, at domes where they are given food, where they don’t have to hunt, and can be in the comfort zone.

Whereas, an eagle is kind of solitary, flies much higher than a pigeon. Does it’s own hunting. Chooses the road less travelled.

Iqbal, as a philosopher repeats this idea, about the nature of human beings. That it’s our nature to choose that high road. The heat which will produce gold.

He was also using these ideas to inspire the Muslims of India, to kick the ass of the British, and to no longer live in slavery, which was called colonization.

Jhapat kar palatna, palat kar jhapatna:

Iqbal describes how an eagle hunts. It does not attack the prey from behind.

The eagle approaches the prey (bird) from the front, and at the first encounter, does a close call, a fly-by. A generous move, to allow the prey to get away, if it can.

Then the eagle turns, and returns to attack again.

Iqbal lived 500 years after Rumi, but often talked to him. Iqbal calls Rumi his spiritual master. In Rumi’s masnavi, there are many amazing stories, with multiple meanings. In his story about the Merchant and the Parrot. The parrot is in a cage. Some scholars see the metaphors as: The parrot is the ego. Or the human being locked in the cage of the body. The way to freedom, is to kill the ego. Like in Buddhism they say, ego is the I, me and mine, which desires so many things. In psychology and in common language, there are many definitions of ego. In sufism, they say annihilate the ego, to be on a spiritual path. Some teachers say the ego is necessary to survive in the world, as a tool. Though any tool can be used as a weapon. Ego defined in that way, is that thing which makes a man unique, it’s what pushes him to compete, to hunt, to win, it’s what drives him. But that ego needs to be reigned in. If a man does not control his ego, his ego will control him. And that ego kills relationship. Perhaps the ego is also what makes a person selfish, confined, limited, on the ground. While generosity makes a person fly like a hawk, like Shaheen?

Thank you for this informative share, Fazeel.

The art of falconry requires apprenticeship, a mentor to coach you into relationship with a raptor. But it’s also understood that your relationship with the raptor is by consent: at anytime the bird may (and often will) simply fly away. Much to learn from these animals.

While this article is not about raptors, the author wrote a memoir about her experience in falconry with a goshawk: H is for Hawk. I’m definitely thinking about picking it up!