It’s always a good idea to start from a place of respect.

When we venture out into areas that are new to us, blushing with the thrill of adventure and discovery, it’s important to remain mindful that we are not the first. What is new to us is rarely ever actually new. If we don’t keep that in mind we may claim things that aren’t ours to take.

Much of the history and legend surrounding the Superstition Wilderness reminds us of this, and I would like to share the little I have learned about the area as this winter’s D&T Grind cohort prepares to head into the wilds of Arizona.

The places we go and the people we meet all have stories. There are traces of itinerant hunting bands roaming the Superstition Wilderness from as far back as 8000-10,000 years ago, depending on sources. Bits of broken pottery and remnants of structures suggest settling by the canal-building Hohokam and the cliff-dwelling Salado peoples around 750 CE. And although the remains may be scant, these were thriving cultures with irrigation practices that brought corn, squash, beans, cotton, and amaranth into the area. They cultivated agave and yucca which they used to weave sandals, mats, and baskets. The Salado in particular were renowned for their pottery which was traded far and wide.

They were architects of great villages and towns that, at the peak of Salado culture, may have supported as many as 10,000 people in the Tonto Basin.

By the 1300s, these early civilizations were in decline. While the exact reasons are a matter of speculation, climatic change including extensive flooding may have challenged irrigation infrastructures to the point where larger groups were forced to break up into smaller bands which may have been absorbed into other regional communities.

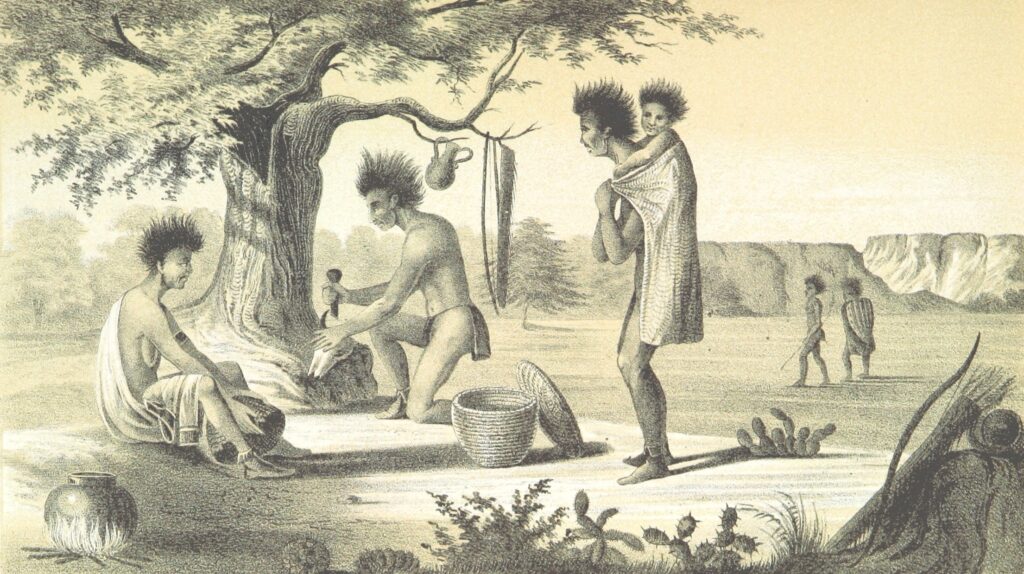

The Tonto Apache and Yavapai moved into the area in the 1500s and their respective legacies remain the more contemporary indigenous influence. Unlike their predecessors, these were hunter-gatherer tribes, building only temporary farmsteads and rancherias as they fanned out across the region.

For 300 years they lived relatively undisturbed, but then gold was discovered in 1863 by the Walker Party.

Everything changed.

What followed was a predictably loathsome manifestation of greed and cowardice as the indigenous people were herded, slaughtered, or otherwise forcibly transferred out of the area to make way for prospectors and their interminable digging.

Much of the contemporary local lore is a representation of our endless fascination with hidden riches. Secret mines, crazed prospectors, wild mountain-men, bandits, ghosts, conspiracies, cryptic maps, and buried treasure are the legends that continue to swirl around the Superstition Mountains. The stories we continue to tell are mostly the ones about gold.

But I take the position of teacher and local historian Tom Kollenborn:

The real gold of the Sonoran Desert region is in the open space that has survived development, and the Superstition Wilderness Area is one of those real treasures.

And I’ll expand upon it. While lust for gold is what continues to draw people and their imaginations to the ‘Supes, I am convinced that with humility and respect we can establish the same kind of relationship with the area that nurtured entire populations before us.

In so doing, we may also find hidden riches within ourselves and each other.

Leave a comment below for posterity or join us in the D&T Chautaqua Discord to discuss this post with other adventurous spirits from around the world.

This was very informative and much appreciated. I have so much respect for the first people of these lands. Their simple existence and life style.

It’s so sad how mans. Greed for land and minerals have wiped out an entire culture and people

I am so looking forward to walk the trails like they did so many years ago.