We feel it in our bones.

Something isn’t right. We know that we get up early. We know that we spend most of our precious, limited time in the service of corporations. We know that our work responsibilities often have us in bed later than is optimal, and the limited sleep we might get is interrupted by the anxiety we feel concerning our pile of debts and obligations, which seem to grow despite our daily toiling.

We work until our mid 60s, when the specter of our infirmity is anticipated by corporate algorithms to likely compromise our productivity. And so we are forced into retirement at the very moment when our long-neglected health starts to tell on us. Trips to the doctor become referrals to specialists which lead to invasive diagnostics and increasingly complicated procedures that land us in the hospital, burying our families in medical expenses even as we are laid to rest. There will be little to no inheritance to comfort the next generation after our accounts are finally settled.

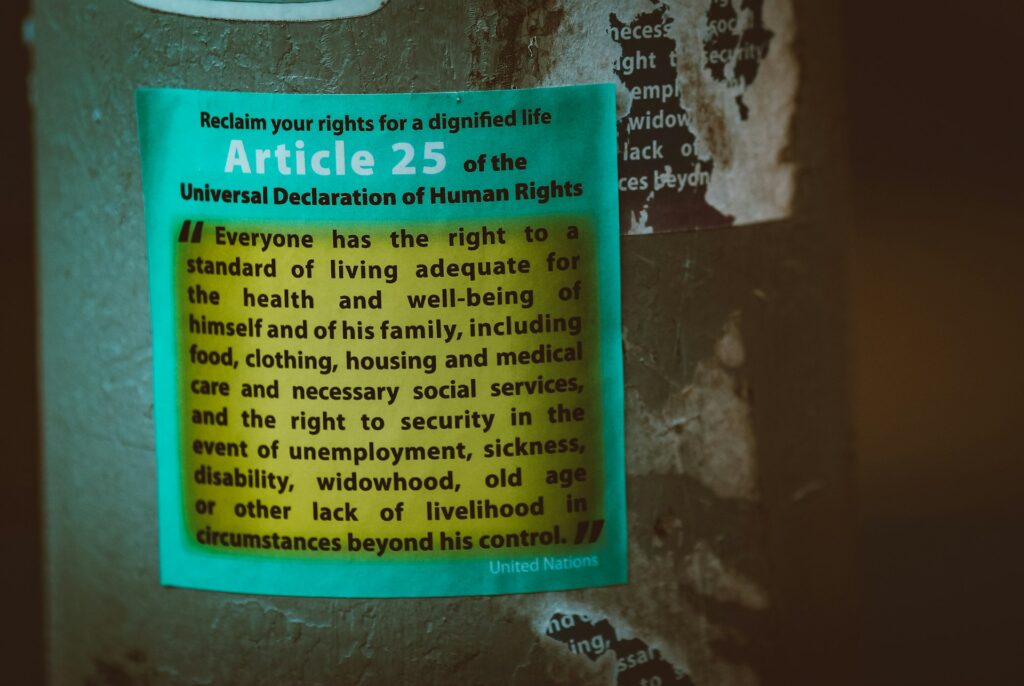

But if we can put some food on the table while alive, and keep a roof over our heads, then we are indeed the lucky ones. Around the world, the men, women, and children whose efforts allow us access to the latest in fast fashion and cheap tech will earn only a fifth of what they actually need to survive. Our relative comfort requires that we quite literally take the clothes off of their backs.

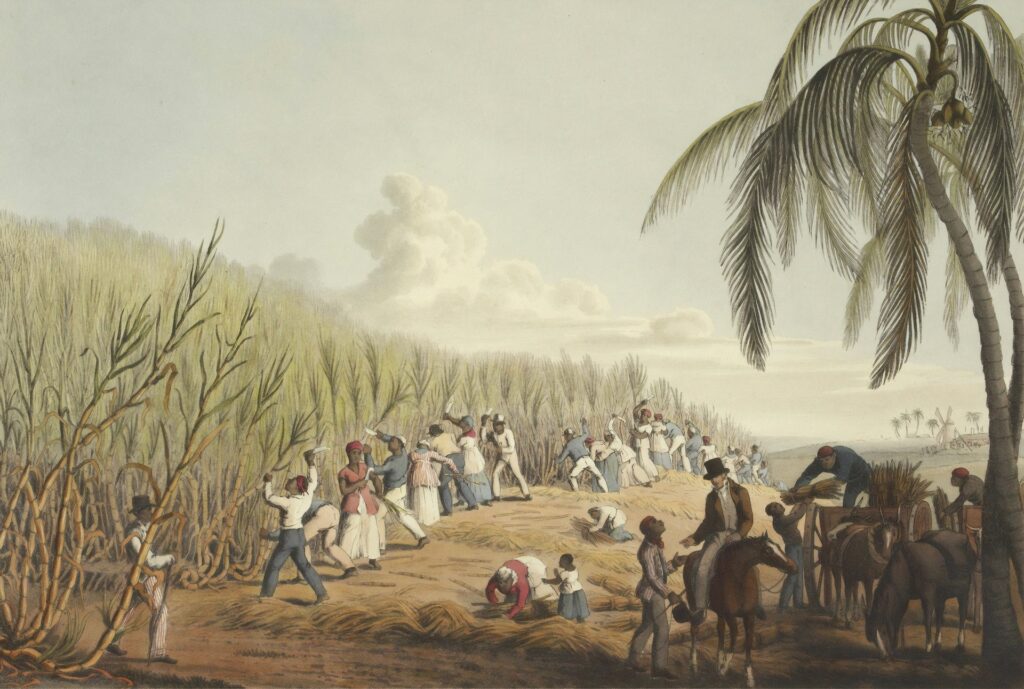

Slavery

This is not new. Slavery has always been the beating heart of the capitalist engine.

“American slavery is necessarily imprinted on the DNA of American capitalism,” write the historians Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman. The task now, they argue, is “cataloging the dominant and recessive traits” that have been passed down to us, tracing the unsettling and often unrecognized lines of descent by which America’s national sin is now being visited upon the third and fourth generations.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/slavery-capitalism.html

The development of corporate hierarchies, the adoption of fiat currencies, the establishment of our corrupt and convoluted banking system, and the battle cries of our profit-driven war machine can all be traced back to America’s plantation system. The cotton fields of the American South provided the garment factories of the American North with the cheap, raw materials that made wealth aggregation possible for the free white men at the top. And when the fields went fallow, the federal government simply authorized the violent displacement of indigenous people to appropriate land for more planting.

American Capitalism, with its colonial pedigree, rewards brutality, and an unconscionable amount of money is made off the labor of the poor and disenfranchised. Most of us will never be rich simply because we have a conscience. Working within a morally-destitute capitalist model robs the spirit of material ambition.

But there is nothing inherently wrong with making money, or even a lot of it. As Muslims, we are tasked with the stewardship of creation. This includes not only environmental and ecological management, but also the curating of principled, affluent communities. In order to be of predictable, consistent, and reliable service to others, we must be more than merely solvent. We should ideally be quite comfortable. Our economics must be considered.

Nonprofits Suck

The knee jerk response from Muslims (and other religious groups) to the ugliness of capitalism is to establish a nonprofit. We think that’s a disingenuous copout. It’s an uninspired attempt to communicate to the public that your organization needs money, but that you’re not in it for the money. Except that you are, because most nonprofit administrators are expecting to be compensated for the services they provide. But these are services that do not lend themselves necessarily to monetization, and so the hard work of solving this conundrum is offloaded onto the public through the creation of a nonprofit entity that solicits endlessly for donations, often through appeals to guilt or religiosity.

It’s lame, especially so at scale.

Why not provide goods and services that can be monetized and do that well enough to establish a charitable foundation? Sure, you might have to close the gap here and there with appeals to the people, but at least you’ve cultivated some degree of trust, credibility, and respect by assuming primary responsibility in the funding of your own noble idea.

As business owners, the Dust and Tribe team thinks about this a lot. We’ve had conversations with many of our participants over the years, soliciting feedback and spitballing revenue models that are sustainable, practical, equitable, and ideally, inspiring. We ran operations initially at cost and then, for most of our history, at a loss. Although not entirely by choice, losing money as we refined our approach to monetization felt a whole lot better than fleecing the public as we figured things out.

Not that we have figured things out. At least not entirely. But we’ve established a few important tenets, guardrails that we would like to present now for our own accountability and for the consideration of others interested in establishing an alternative to the current rapacious capitalist system that exists only to empower the few and control the many.

Principles and Practices

These are our three anti-capitalist governing principles:

An ethical business balances communal wealth disparities. By focusing on quality, goods and services are offered at a premium price, appealing primarily to those persons with a surplus of resources. The wealthy exchange their money for product, and some portion of profits are cycled back into the community. Money is redistributed in the form of charitable contributions, the allowance of sliding-scale payment schemes, or carefully considered sponsorship deals.

An ethical business enriches those who support it. We can’t be in it exclusively for ourselves. Whether through their labor or their patronage, all who encounter an ethical business should come away better for it. The products and services offered have socially redeeming value. The wages and compensation offered are not only equitable, but generous.

An ethical business rejects material growth as a measure of success. Resources are finite. Any metric of success that defies this reality is simply greed rationalized. The only metric necessary for an ethical business to determine success is their ability to meet expenses while adhering to principles. Once this is accomplished, there is no need to do more.

And these are our three anti-capitalist practices that we have put into place based on the above principles:

No engagement with social media platforms. They exist to aggregate and manipulate social behavior. We refuse to participate in exercises of mass delusion, deception, and censorship.

Limited merchandise. Dust and Tribe is in the business of hosting wilderness experiences, largely as an antidote to numbing urban materialism. As such, there is little room in our ethos for selling merchandise, except insofar as such items might support a richer wilderness experience.

Sharing profits. Dust and Tribe offers an 80/20 profit sharing arrangement to our lead facilitators, a model validated by Islamic religious tradition, grounding us in the deep morality of prophetic precedent.

Here’s what we mean.

Before prophethood, Muhammad, may the peace and blessings of God be upon him, was commissioned for the conveyance and distribution of goods by a successful merchant, our lady Khadijah, in what was likely a profit-sharing arrangement. After prophethood and his emigration to Medina, another profit-sharing arrangement was revealed to him:

And know that anything you obtain of war booty, indeed for God is one fifth of it and for the Messenger and for his near relatives and the orphans, the needy, and the stranded traveler . . .

Q8:41

For the fractionally-challenged, one fifth is 20%, the amount reserved for Islamic leadership to be used in the administration of their public works, with the remaining 80% for distribution among those who played an immediate role in the acquisition of said wealth. This model was good enough for them and it’s certainly good enough for us.

The sharing of profits within Dust and Tribe includes a portion committed to the local indigenous Nisenan people as a land-use fee.

Not Perfect

We haven’t fleshed everything out, not by a long shot. We have lots more work to do in advancing an ethical business model, but we’re trying and certainly open to feedback and criticism. We’re small enough that we can keep playing quietly with our ideas until we feel we’ve got something really nice to share. What we’ve presented here is the best we currently have to offer.

We certainly have other thoughts, but nothing worthy of codification at this time. They haven’t been properly workshopped and right now they really don’t amount to much more than biases, like our aversion to the monetization of knowledge and artistic expression. Selling information and art is deplorable, with the current state of copyright law proof enough of how ugly things can get when we decide to put a price on these things, not to mention the bloat of the entertainment and “coaching” industries.

But that’s grumbling for another time.

In the meantime, enjoy this information while it’s still free.

Leave a comment below for posterity or join us in the D&T Chautaqua Discord to discuss this post with other adventurous spirits from around the world.

I’m consistently inspired by your work, mashallah.

The beginning of this article is EXACTLY what’s been on my mind for the last several years, and keeps me depressed. It’s exactly as you said, slavery but in a different form. It’s become to expensive just to live, with rising costs of housing, food, etc, and so more and more people are forced to keep working higher and higher hours. Almost makes you wonder if that’s intentional that things keep becoming more expensive… anyway, this is all going to reach a boiling point, at which it will not be sustainable and a breakdown of society will occur. May Allah protect us.