I’m going to do my best to explain this.

It’s absolutely fascinating, but pretty academic. And I’m not even sure that I understand it all, but the little bit that I feel confident about has completely reified my conviction in Divine revelation as not only possible, but uniquely necessary.

All of this is based on the work of Leonid Perlovsky, a theoretical physicist with connections to Harvard and the United States Air Force. I came across his papers years ago while researching theories on the evolution and function of music, something we will touch on later in this discussion.

Out of respect for Dr. Perlovsky, it should be said that we are not aware of his position as it regards revelation. We have written to him, so far without response. For now, we are drawing our own conclusions from the patterns he has arrived at through his investigations into cognition and language. For those interested, here’s a link to the paper that we will attempt to explain.

The plan is to share how the fascinating interplay of language, cognition, and emotion enhances our opportunities for survival. Then we’ll get into how revelation fits into all of that.

Stay with us, because if we’ve understood his work correctly, we think we’ve stumbled across an argument propping up the Qur’an specifically as a life essential.

It’s complicated, so we’ll start with something easy.

Instincts

What we recognize as instincts can also be understood as our awareness of essential need. Through our brain’s interpretation of signals received from sensors throughout the body, we come to recognize that we are hungry or tired or scared. How we go about addressing those needs is actually pretty involved.

Because we can’t eat just anything. Instincts alone do not tell us what food even is or, once that’s cleared up, what foods might be beneficial or harmful. And managing fear requires a whole host of considerations and decisions, all of which we need to sort out even as our bodies succumb to the physical effects of our instinctual threat alarm. Rising blood pressure and heart rate, sweaty palms, and hyperventilation will rob us of the clarity we need for an optimal, survival-enhancing response to the locus of our alarm.

Figuring out how to meet our instinctual needs is itself an instinct. Specifically, it’s what Perlovsky calls the “knowledge instinct.” And here is how he proposes that it works:

Very early on, we form concept-models in our mind, ideas sculpted by our primal sensory experiences. Mother’s milk, for example, has a certain color, scent, flavor, and texture. We link these sensory perceptions to an evolving, if not somewhat fuzzy, concept that our brain gradually hardwires as “food.”

This goes on and on, with indistinct ideas for “mother” and “father” and “safety” and “spoon” gradually taking shape. However, the accuracy of these ideas requires some kind of ongoing confirmation for us to build confidence, and so we use our senses to validate these evolving ideas. This confidence can also be understood as knowledge, which Perlovsky defines as “the measure of correspondence between mental representations and the world.”

The knowledge instinct is an innate drive to maximize that correspondence in two ways: gathering information through our senses (and other means which we will soon discuss), and refining our ideas by compositing all of this gathered information into some kind of unified comprehension.

But how do we assess the correspondence between our evolving mental representations and the world?

Life moves very quickly. Just when we’ve finally wrapped our heads around mother’s milk as food, the warmth of the feeding embrace, the softness of her breast against our cheeks, and how this will all add up very quickly to a sating of our hunger, we get a spoonful of strained peas pushed in front of our face.

Emotions

Those peas will create feelings.

In Perlovsky’s words, “emotional signals evaluate concepts for the purpose of instinct satisfaction.“

We’ll sniff those peas. With some encouragement from that person aligning with our idea (concept-model) of “mother,” we might even poke a tongue out for a taste. And if our sensory experience of these peas is too far removed from our idea of “food,” we might cry. The lack of correspondence may overwhelm us. The lack of harmony between our immediate perception and our mental representation of “food” may bring feelings of confusion, fear, or frustration.

We are hungry.

Our instincts are driving us toward the acquisition of food, not this weird green slop.

But maybe our senses tell us something different. Maybe mom has been eating a lot of peas herself. Some of that flavor and scent is on her lips when she kisses us, or maybe that vegetal essence has found its way into her milk. The peas are unexpected, but somehow familiar.

We feel intrigue and curiosity. Mother is smiling and cooing just like she does when she gives us her milk.

Encouraged, we taste it.

It’s not bad, and after a few more spoonfuls, our brains get to work expanding our concept-model of “food” to include, not only this new substance, but also the possibility that there is so much more to learn about food, and really, about everything.

From that point forward, we’re filling our mouths with whatever we can get our hands on, with all kinds of resulting connections registering our new experiences through rapidly expanding neural networks. Much of this is now mediated by emotions: the curiosity we feel about a new object, the trepidation that mother burns into us through a scolding, and the miserable or pleasant sensations that arise from this mouthing behavior.

To the extent that our feelings affirm harmony between our external senses and our internalized concept-models, our ideas are reinforced and priority is given to what we are experiencing as a means of satisfying a specific need. If we are hungry and presented with a loaf of bread and a brick, our emotions will affirm a correspondence between the scent and texture of the bread and our understanding of food. We will therefore prioritize our selection of bread over the brick for the satisfaction of our hunger instinct.

Where there is a disconnect between our idea of a thing and how it looks, sounds, feels, tastes, or smells, we will feel some kind of emotional warning. This could evolve into surprise or delight, as in the experience of seeing someone cut into what we thought was a tire, revealing it to be a cake. Or it could evolve into revulsion and disgust as foul odors suggesting spoilage fill our nostrils.

What we need to understand before moving on is how all of these things, our senses, our thoughts, and our emotions are all exquisitely linked together to drive Perlovsky’s knowledge instinct, that inborn tool without which we would very rapidly cease to exist.

Language

Up until this point, we’ve limited our discussion of how internalized concept-models of the world are formed to the very primal example of a baby exploring the world through senses. But putting things into our mouths will only get us so far. It’s not long before things get complicated.

As we get older we start to notice patterns and relationships , things that defy exclusively sensory apprehension. The concept-model of “sister,” for example, doesn’t have a particular taste or smell, even if the person holding the title of “sister” does. There are other people who may look or sound very much like “sister,” but there is something beyond the senses required to affirm the unique feelings experienced in the relationship we have with “sister.”

That something is language.

Before we move on, we need to point out just how unique language is in the created world.

In all other animals capable of vocalizing, there is very little volition. They do not decide when they will speak. Rather, the sounds they make are linked to their experienced state.

A squirrel has a number of vocalizations, some indicating alarm, some declaring territory, and some reserved specifically for mating. But none of these sounds are interchangeable by the squirrel. They do not have the ability to sound an alarm in the absence of threat. Their instinctual and emotional centers are linked so precisely to their vocal apparatus that once they feel and recognize danger, for example, there is only a very specific set of sounds they will make.

The precision and rigidity of the squirrel’s neuromuscular sound-generating pathway, from thought to expression, can be considered an entirely synthesized whole. The squirrel is what Perlovsky would call synthetic, meaning that there is an inviolable wholeness and continuity that describes and predicts how the squirrel and other non-human animals will vocalize.

Humans are different.

Differentiation vs. Synthesis

Things are not as synthetic with us. Our instincts, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are interconnected (a very important point that we will come back to), but not in nearly so integrated a manner as the squirrel. Our ability to separate all of these interrelated components of the knowledge instinct is termed differentiation, and language is what drives it.

Unlike all other animals, our ability to vocalize is discreet, distinct from our cognitive and emotional centers. We can choose what we want to say and when we want to say it, meaning that we can explore the world through language in ways that nothing else can. Whereas the squirrel may have a particular sound reserved for the sensing of an aerial predator, a sound that can only be made in observation of the raptor and only with the purpose of warning others, we can talk rather dispassionately about the hawk without feeling the need to run and hide.

Biologically speaking, this is profoundly advantageous. Once the language skill is decoupled from our primal instincts, feelings, and behaviors, we can use it to grasp the world around us and to communicate the concepts within us. This has led to a rapid and unprecedented apprehension of our environment, along with approaches to both manage and manipulate it, leading to humanity’s absolute ascendency over all living things.

This comes at a price, however.

As previously mentioned, the knowledge instinct compels us to not only gather information, but also to make sense of it, to assess for correspondence between what we are learning and how that aligns with our instinctual needs. Our feelings are, in many ways, the measure of that correspondence and all of this was pretty straightforward when we explored the world using only our senses.

Language complicates things.

Language allows us to explore the world beyond our senses, taking us further and further away from the merely instinctual. Even as we acquire more and more information, our use of language forces a separation between our emotional, intellectual, and behavioral selves. We are increasingly differentiated, with the wholeness of our previously synthesized instinctual grasp of the world shattered.

No longer purely synthetic in the manner of the birds and reptiles, flowers, and trees, the knowledge we acquire through our use of language threatens to fracture our psyche altogether.

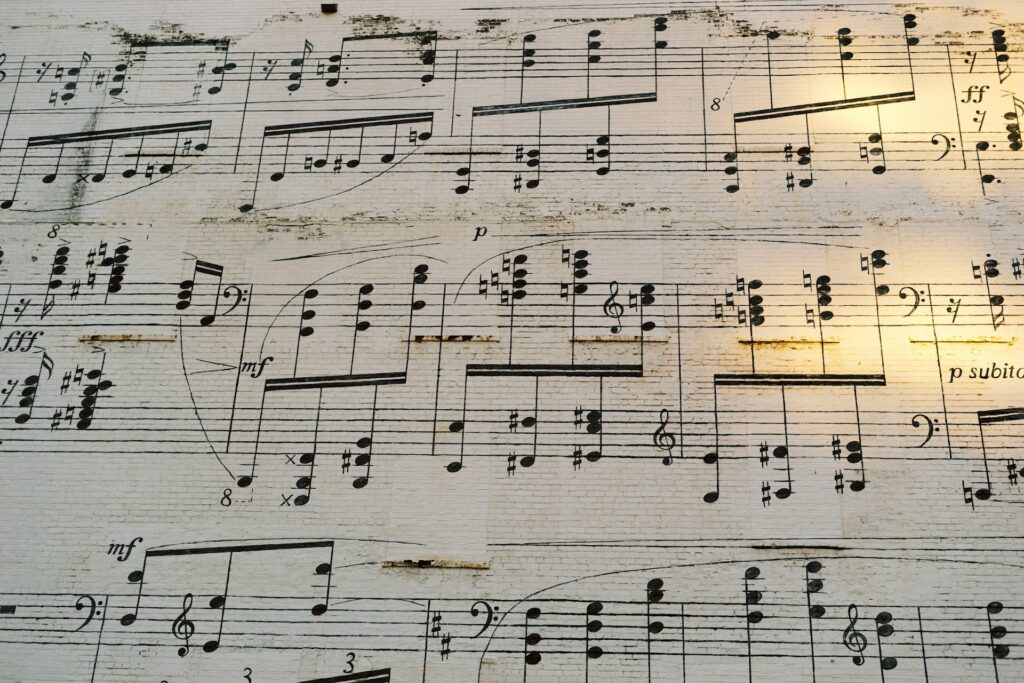

Music

We mentioned Perlovsky’s description of the knowledge instinct as having two components: the gathering of information and refining our ideas by compositing all of this gathered information into some kind of unified comprehension.

Language enhances and accelerates the acquisition of information. But with all of it coming in so fast and furious, much of it challenging or outright contradicting what we thought we knew, we will have tremendous difficulty making sense of it all. Our learning leaves us increasingly fragmented, less and less whole, and this complicates the second aim of the knowledge instinct which is ultimately synthesis: a return to the complete alignment of our ideas, emotions, and behaviors.

Like the animals.

Like the trees.

Like our primal, instinctual, and infantile selves.

There is significant tension between the two aims of the knowledge instinct, this information gathering and synthesizing. Language intensifies this tension greatly, and if we are unable to balance this, we are lost. The result is nothing less than social nihilism and cultural decay.

Because without synthesis, without the opportunity to incorporate all the information that language brings us into some kind of unified comprehension of our existence through the integration of our instinctual, emotional, and cognitive faculties, the knowledge we acquire loses meaning. The frustration we feel in not being able to reconcile the things we learn with our internalized concept-models can erupt into outright hostility, first within ourselves, but eventually with others as we try to force our external circumstances into emotional compliance with our ideas of how things ought to be.

We need to manage the feelings associated with the disintegrating effects of knowledge acquired through language, and, according to Perlovsky, this is why humans create and respond to music.

It’s important to note that the term “music” here does not necessarily imply the use of musical instruments. Perlovsky is framing an argument for the evolution of melody and rhythm, which he and a number of other prominent theorists believe was concurrent with our development of language:

Many scientists studying the evolution of language came to a conclusion that originally language and music were one (Darwin, 1871; Cross, 2008a; Masataka, 2008). In this original state the fused language-music did not threaten synthesis. Not unlike animal vocalizations, the sounds of our voice directly affected ancient emotional centers, connecting semantic contents of vocalizations to instinctual needs, and to behavior.

Pervlovsky 2010

Originally language and music were one. That has changed, but not in a uniform way. Some languages retain elements of their inherent musicality, and with it, all of the integrative power to balance the two aims of the knowledge instinct: information gathering and holistic comprehension. This musicality is often appreciated by linguists by the extent to which a particular language is inflected.

If the meaning of a word can be changed by modifying the sound of the word through the addition of letters or the elongation or shortening of vowels, it is considered highly inflected. If changing the meaning of a word requires additional words, the language is less inflected.

As an example, to say “this book belong to those women” in English (a weakly inflected language) requires six words. This same statement in Arabic (hadha kitabuhunna) requires only two words. Arabic is highly inflected with the consequence that much more meaning is encoded into the sound of each word than is the case for less inflected languages.

This is what we mean when we talk about the inherent musicality of language and how some languages have preserved this more fully than others. The significance of this lies in the relationship between sound and feeling, between feeling and instinct, and the integrative possibilities of these more inflected languages to sonically soothe our psychic fragmentation:

Quoting Perlovsky:

Semitic languages (and in particular the Arabic language) are highly inflected. The inflection mechanism (also called fusion) affects the entire word’s sound, and the meaning of the word changes with changing sounds. In addition, suffixes control verbs and moods. Therefore, sounds are closely fused with meanings. This strong connection between sounds and meanings contributes to the beauty and affectivity of Classical Arabic texts, including the Qur’an.

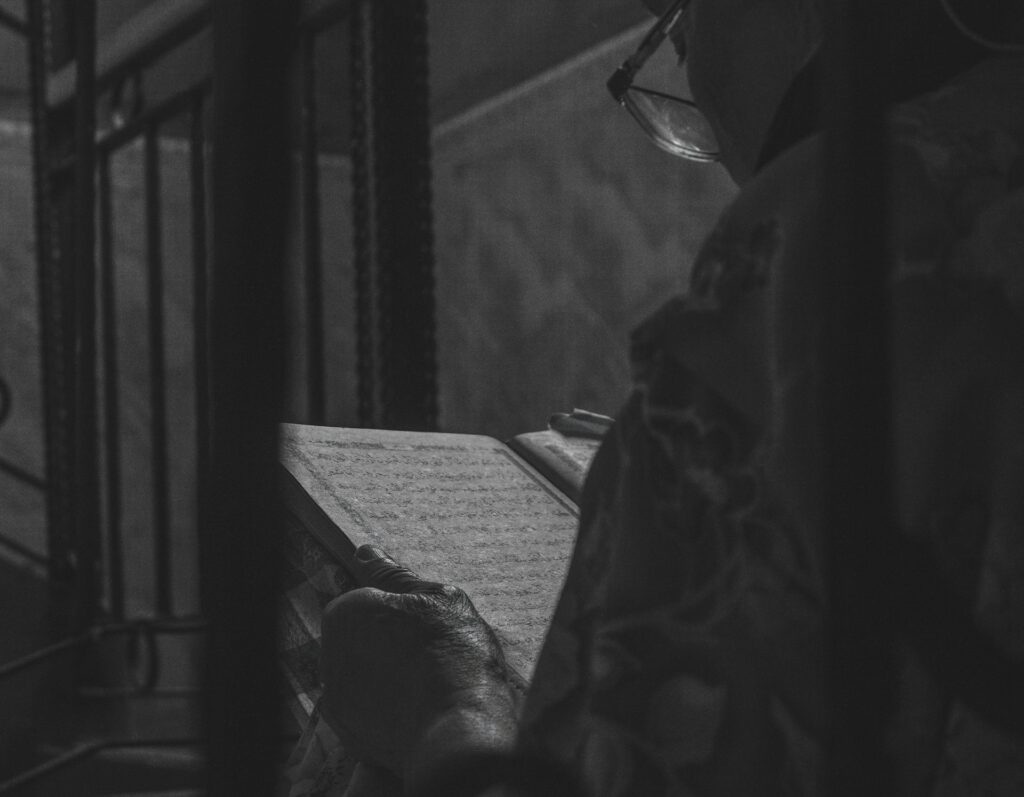

The Qur’an

There is more to Perlovsky’s intuition about the Arabic language and it’s function as an integrative balm. His thoughts are limited in this paper to a consideration of linguistic inflection and, to be sure, there are languages still more inflected than Arabic. But what is utterly unique to semitic languages (Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic) is their triliteral root system, where most words can be reduced to three consonants, the sounds of which are linked to an entire “family” of ideas.

In our earlier example of “this book belongs to those women (hadha kitabuhunna),” the word for book can be reduced to the three consonants k-t-b. This combination of sounds (ka/ta/ba) carries a number of interrelated meanings: book, writing, library, office, desk, clerk, writ, decree, and even fate as in the phrase, “so it is written.” Specific meanings are clarified through the addition of vowels, prefixes, suffixes, and even the doubling up of consonants, but doing so does not change the richness and breadth of the cognitive and emotional associations of the sound ka/ta/ba. Whatever form it ultimately takes, we cannot overstate the integrative power of the Arabic language to continually deepen our synthesis, to continually reinforce our sonic (and therefore emotive) connections to meanings that have recognizable instinctual value.

The sound and form of the Arabic language is psychic medicine, balancing the disorienting consequences that attend our pursuit of knowledge.

The Arabic Qur’an is a book that can be read and studied, but its utility in the life of a Muslim has always been associated with its recitation. There are rhythmic rules that must be learned for one’s recitation to be considered canonical, and this makes sense now that we understand the relationship between sound and meaning. The reciter may have a personal interest in learning from the book, but she also has a communal responsibility to preserve the meanings of the text for others.

Conclusion

We come into this world trying to make sense of things. This is a matter of survival.

Initially, our instincts guide us through this process. Driven by our senses and mediated by emotion, we gradually learn how to receive life’s essentials.

Our exploration of the world is both enhanced and complicated by language, a faculty divorced in humans from the emotional and instinctual centers of our consciousness. We are compelled to question everything around us, but also challenged to reconcile what we are learning with what we thought we knew.

This tumultuous sea of ever-evolving knowledge keeps us teetering between the crest of enlightenment and the trough of despair. The existential confusion and anxiety of our predicament threatens to overwhelm us.

We could decide that none of this matters. Or we might manage this crisis with a leap of faith:

There is no doubt that this book is a guide for the pious

Q2:2

The book is in Arabic, a living language carrying within its recited form a primal musicality. The melody and cadence of this recitation calms the emotions even as discovered meanings thread their way through our fractured minds to weave healing associations. Our experiences are confirmed, conditioned, and contextualized.

Integrity is restored.

At least for the moment.

Leave a comment below for posterity or join us in the D&T Chautaqua Discord to discuss this post with other adventurous spirits from around the world.

One Reply to “The Qur’an is a Survival Manual: A Neurolinguistic Argument”