What would happen if I invited Muslim men affected by divorce out to the desert to climb rocks?

We often talk about a troubled marriage as being “on the rocks.” It seems there is a natural connection there, but what is the link?

I wanted to find out, so I put out the invitation. That was back in February 2020. I’m going to tell you the story, but first I should tell you why it even matters.

I’ve been divorced a couple of times. My first marriage lasted less than a year. I was in my early 20s and she was a really nice, church-going woman who thought she might try out life as a Muslim. Well, that was over before it started, and I’m happy to say that we still check in on each other from time to time.

The stakes were much higher with my second divorce. That was a 15-year affair with the future of four precious daughters in the balance and it’s been a very hard road.

A road, that I suspect would be made easier if my faith community were more comfortable with divorce. It’s a curious thing that stigma around divorce would even develop among Muslims seeing how divorce is so directly and compassionately explicated in the Qur’an, our foundational text. Sanctioned polygyny and numerous examples from the lives of early Muslims suggest an historical understanding of marriage as much more fluid than the rather catholic version endorsed today, but the stigma is there. And that stigma can turn a challenging transition into a crippling liability.

That doesn’t sit well with me and it seemed that a discussion was in order with men who have some experience with marriage gone awry.

But men come together best when we’re doing things. You don’t just call up the guys to have a conversation. There needs to be a pretense, something physical that burns off the energy we all use to hold up our very heavy shields. We need an adventure.

The work of Dust and Tribe can be boiled down to one idea: we grow through adventure.

But what is growth? And how do you define adventure?

The easier question is probably the latter. EVERYTHING is adventure. The whole thing. Cradle to grave. One big adventure. And certainly, navigating a difficult divorce in the absence of communal support is an absolute adventure.

But the question of growth. Growth, I’ve come to believe, is the point of adventure. It is why life unfolds the way it does. Each moment reveals itself in sequence, and we never really know what’s going to happen next. We anticipate the moments to come based on probabilities and patterns, but we never really know.

Growth, more specifically, is the progressive, deepening realization of that point. That we don’t know. That our lives are predicated on a kind of unacknowledged faith that everything is going to work out the way we imagine. Growth is coming to terms with the centrality of faith in our lives. Growth, I would say, is coming to believe.

I brought the idea of a divorce-themed adventure to my dear friend Todd. He’s a divorced man and an avid rock-climber, and together we hit on rock-climbing as a wonderful metaphor for the divorce experience.

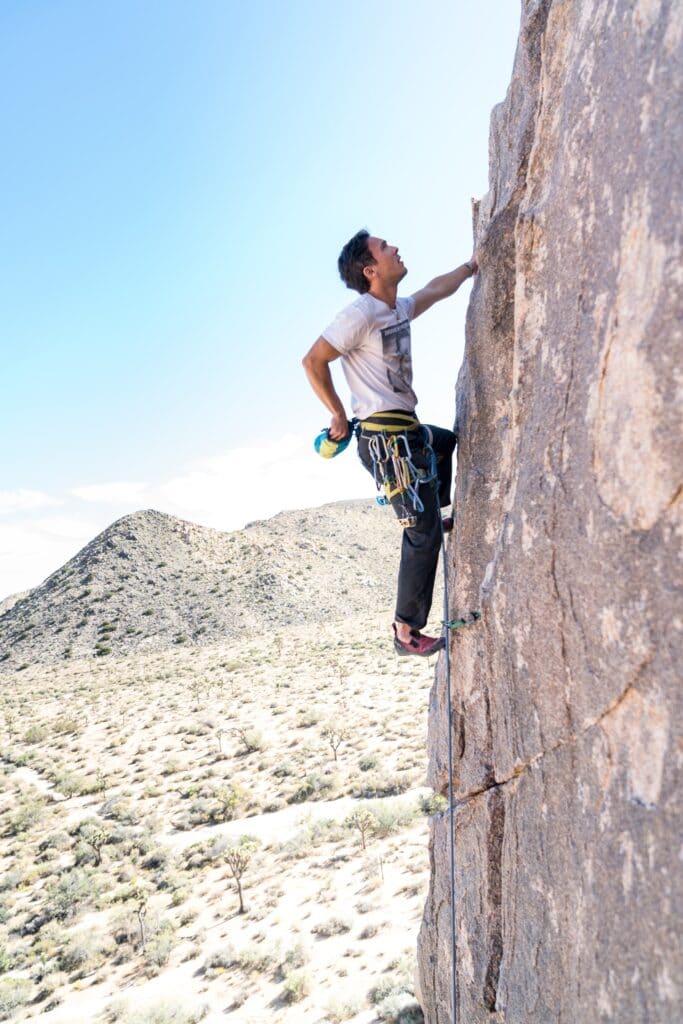

Rock is cold and it’s hard. It’s indifferent. The rocks that you climb are enormous and intimidating. The rocks just are, and there is nothing you can do to change that.

But with care and diligence and guidance and persistence, you can eventually find your way up and over.

You start at the base of the rock, reaching, searching with your fingertips. Your fingers catch, and with every new hold, trust and fear explode in your chest. Will you freeze? Will you fall? Or will you inch just a bit higher? And if you do, then what?

Rock-climbing is a harrowing dance with the unknown. It was the perfect metaphor.

I put out the invite and there was a lot of buzz and conversation at first. There were people in and then people out, and in the end there were five of us, all men affected by divorce. Some of us were married. Some of us were witness to the dissolution of our parents’ marriage. But we are all, in some way, recalibrating around radically shifted relationships.

There was me and Todd. Another experienced rock-climber, his name was Mohamed, he would join us along with Bilal and Said, two younger men whose fathers were estranged in the aftermath of divorce.

The plan was to camp and climb in Joshua Tree National Park.

The desert is beautiful and Joshua Tree is a particularly magical place. Todd got there before sunrise and the rest of us were there with the sun still low enough on the horizon that the rock formations were throwing long, dark shadows, cooling the gusty air. Those stones felt like ice.

Todd pointed to some rocks, “We can warm up on those.”

My heart sank. Oh my God. These rocks were HUGE. “Warm up,” he said. He was pointing to impregnable WALLS OF DEATH.

But the company that we keep makes a difference in how we come to see things, and the cluster of formations in our immediate vicinity would become the place where I roped in and climbed for the very first time.

We were top-roping, a style of climbing where the climber is attached to a rope that runs up to an anchor point at the top of the climb and back down to your partner, the belayer, who’s at the foot of the climb. As you climb, your partner takes up the slack, like a pulley system.

Todd and Mohamed were our facilitators. They had only just met that morning, but they were quick to establish the flow and communication that would serve our little group very well through the weekend. They were the men climbing up the backsides of the rocks to secure the anchors and run the ropes. Our safety and success depended on their vigilance and expertise.

And here you can start to see the metaphor establishing itself. This was my first climb. In order for me to ascend, I had to trust the wisdom and guidance of men with experience.

But trust, I found, did not come easily. There is an instinctual resistance to climbing really high rocks. We are hard-wired for self-preservation and, beyond a few feet for the purpose of exercise, there is no merit in climbing that can be immediately sensed by our bodies.

So in order to climb, one must move past instinct and into a place of trust.

We marry out of instinct, a desire for procreation or sexual expression that requires, in the Islamic faith-tradition, a contract between man and woman guaranteeing that certain rights and obligations will be honored, whether the marriage lasts or not.

But the assumption, the intention, and the aspiration for many of us is that the marriage will last. And when these domestic expectations are challenged, that preserving instinct kicks in hard to keep us locked into what is familiar and desirable. Because what is familiar is understood by us on an instinctual level as safe.

Releasing instinct, moving away from what is familiar and into new, unmapped terrain is horrifying.

But I had Todd and Mohamed and they promised me over and over and over again that they were holding me. That they wouldn’t let me go.

And so I climbed. Just a little at a time. But I climbed.

And when I watch the video of me climbing, you can absolutely see the lack of trust. You can see the burden of instinct as I hug the wall like a frightened slug. But I won’t be too hard on myself because reshaping expectation at the instinctual level takes practice and support and mentorship. It wasn’t pretty, but it was a start.

Watching experienced climbers is a revelation. They dance. They flow and stretch with exultant movements that take them from one hold to the next. You are a witness to their discipline and practice, their patience and their work. A good climber is someone who learns to trust well enough that new instincts establish themselves. They have a revised understanding of what is familiar, of what is safe.

Perhaps like a man without a father who has found a mentor. Or like a father forcibly estranged from his children who has found away to build and maintain a relationship with them despite all odds. These are scenarios so radically different from what was once considered familiar and desirable. But once you put your trust into embracing the moments you find yourself in rather than wasting energy on tantrums about the things you once had, you are halfway up the rock.

But that requires the company of others who have been there, other men who can tell you with confidence that you’ll be OK.

The rest of the climb requires a belief that what lies ahead is better than what came before.

We didn’t go to Joshua Tree to fix anything or to solve any problems. We weren’t hoping to arrive at some master plan for taking control of our lives so that we might guide divorced men everywhere. We were just there to climb rocks. We were there to tell our stories. We were there to trust and to listen. And to learn what we could from the rocks that God in his Infinite Wisdom left there for us to climb.

We camped there for a couple of nights. We ate together and we talked and we climbed. And we also prayed together, growing as we must into believers.

I won’t speak for the other men. But I will share that my own experience tethered to those rocks was equal parts horrifying and illuminating. I learned, very quickly, that fear comes much more easily to me than trust. I learned that I will become emotionally exhausted well before my body has reached its limits. I also learned that good company can make up for a lot.

But for all the awareness and company, it will still always be about me and the rock.

One Reply to “On the Rocks”